Back to Part 1 – Yin-Yang in Taijiquan practice

Forward to Part 3 – Yin-Yang in Taijiquan applications

Yin-Yang in Taijiquan practice

To understand the way Yin-Yang is played out in Taijiquan, a practitioner needs to examine the forms and the applications that lie behind them. Applications provide the intent and are the reason why Taijiquan is performed the way it is.

It’s within the applications that one can best see both Yin–Yang and energy exchange in action.

The table shown left lists some relative characteristics of Yin and Yang which can be looked for in any given Taijiquan movement. This is not a reversion to opposites, it is simply a list of relative qualities that can be observed when studied in conjunction with a chosen move or posture.

The basic principle (as stated in Part 1) is that Yin and Yang are forever changing, one into the other in a continuous cycle. It follows then that the one will ultimately be overcome by the other simply because whatever increases or expands (Yang) will run out of energy and collapses into its opposite (Yin). Therefore, while Yang energy can overwhelm Yin energy, Yin can overcome Yang by the action of yielding and allowing Yang to exhaust itself. It is the way of yielding and what one does next that underpins Taijiquan applications.

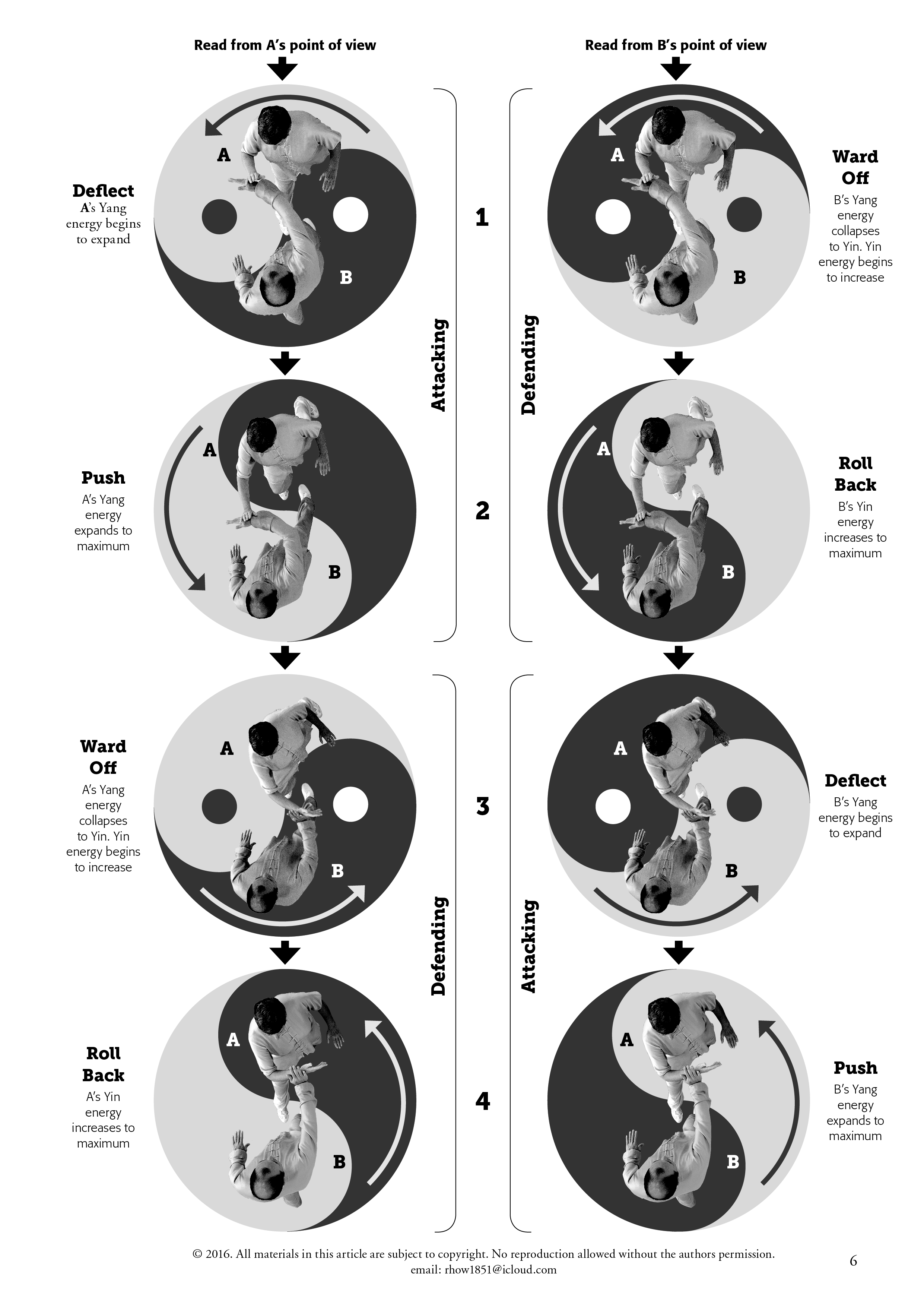

The following illustration shows a series of diagrams depicting the first four stages of the first single hand movement of Push Hands, overlaid on the Yin-Yang symbol. Shown in this fashion, it is as concise a way as any other to demonstrate how Yin-Yang energy exchange actually works. The reason for choosing push hands over any other form or application is (to quote from Yang Chengfu’s The Essence and Applications of Taijiquan) as follows:

Taijiquan uses the practice of push hands (tuishou) to convey the meaning of its applications. Studying push hands is learning how to sense energy (jue jin). Once one can sense energy, it will not be difficult to understand energy (dong jin).

That just leaves the question of defining what is meant by the term ‘energy.’ In traditional Chinese martial arts terms it usually means ‘chi’ (qi). In strict Western scientific terms there are many types of energy but chi is not one of them—its existence being denied by lack of (scientific) evidence. The whole subject of chi, its existence or non-existence is much written about and discussed elsewhere but whichever way the term ‘energy’ is understood, be it Eastern traditional or Western scientific, the principles of Yin–Yang and the manipulation of energy are equally applicable.

Push Hands sequence explanation:

(Note that this is not a set of instructions on how to perform push hands so the sequence listed for ‘A’ differs from convention vis; ward off, roll back, deflect and push. What is described is solely intended to illustrate how Yin–Yang can be observed in a practical, rather than theoretical, way).

1. Deflect. After the initial midway starting point (the neutral position) B elects to attack A by pushing forward. Any move coming towards you is going to be Yang in nature and A can deflect this attack because B’s Yang has quickly collapsed (gone past the point of maximum effectiveness—see opposite). As there is now nothing left in terms of energy in the attack, very little effort—a simple turn of the waist-—is all that is required to deflect it. A is now attacking B. A’s Yang energy begins to firm, expand and advance. A’s stored and hidden energy has been revealed.

However, for B the opposite is happening, A’s deflection is B’s ward off. Because B chooses to stick with the deflection, B’s Yang energy has become Yin and starts to increase. B is now defending.

2. Push. A now continues the attack with a direct push, increasing Yang energy to point where it will soon reach its maximum potential. B yields to it by retreating (roll back). B is defending.

3. Ward off. Up to this point A has been attacking B, but now A’s store of Yang has gone past its point of maximum effectiveness and has collapsed into Yin. B has been able to deflect the attack for the same reason as for A in the 1st move. A is now defending and B is attacking.

4. Roll back. In rolling back, or yielding, A’s own store of Yin energy (what will be used to retaliate) increases. This is known as ‘absorbing.’ Retreating also hides A’s intention, it gives nothing away as to the kind of response that will be made to B’s push. B is attacking.

Observations

When Push Hands is performed correctly, the hand of defender doing roll back is moving very slightly ahead of the hand of the attacker doing push, but without loosing contact. This is called following. In addition, the waist of the defender is acting like a wheel in a horizontal plane. The net result is that the attacker meets with no apparent resistance but is being deceived, because the defender is actually absorbing the attacker’s energy before deflecting it.

Newton’s Third Law of Motion states that every action has an equal and opposite reaction but in push hands this seems to be defied because the force of an attack finds nothing to act on—the target has moved away as fast or as slowly as the attack proceeds. Hence the statement:

If my opponent does not move, I do not move. If my opponent moves, I move quicker.

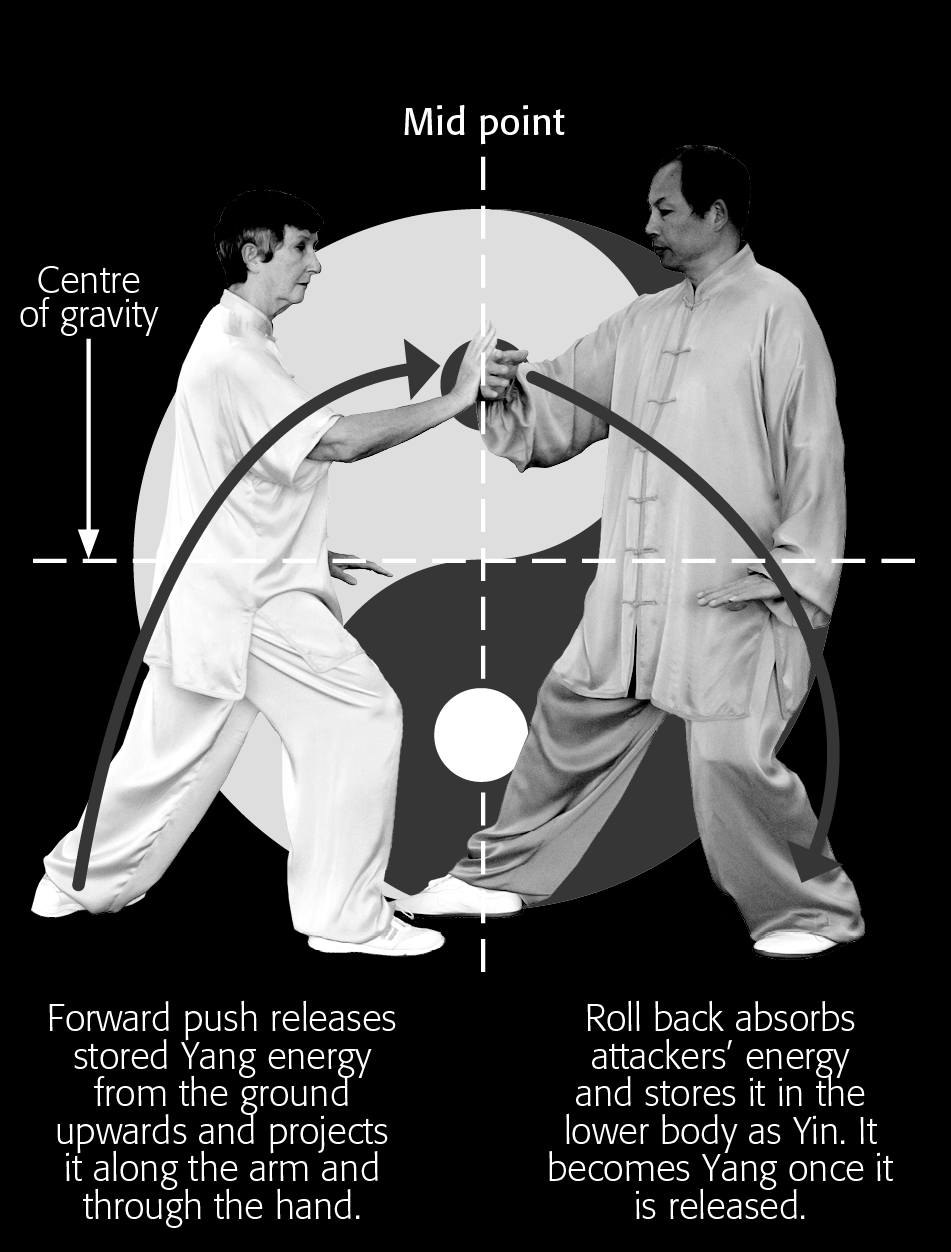

The consequence of this that a practitioner of Taijiquan never initiates an attack, only respond to one. That will then accord to the principle of Yin overcoming Yang since Yang energy coming towards the defender is absorbed by rolling back and stored as Yin in the lower body and legs. Assuming that all ten principles of Taijiquan are being applied correctly by the defender they will be able to respond with a counter attack, releasing stored Yin energy as Yang and be able to do so with minimal effort since the attacker’s force will have been dissipated.

The direction in which the response is made should always follow the direction of the attack. For instance, if a punch is driven upwards towards the defenders face then the deflection would take that punch away from them in the same upwards direction. Attempting to alter it—for example, from upwards to downwards—would require force (Yang fights Yang) whereas maintaining direction requires minimal effort (Yin defeats Yang). Push Hands routines are many and varied but always the same principle concerning deflection is maintained, no matter what angle or direction an attack comes from.

Push Hands it is said, teaches an understanding of energy, therefore it must also teach an understanding of Yin-Yang. To understand energy and Yin-Yang a practitioner will have to learn how to sense it—when it is one, and when it becomes the other. He or she have to be conscious of where energy is stored, when and how it should be released, in what direction and when it has reached the point of change where a defence can become an attack (Yin becomes Yang) or visa versa, an attack ceases and has to change to a defence (Yang has become Yin).

In Push Hands the sensing (often referred to as listening) is performed by the hands. With the legs pushing backwards and forwards and the waist performing the turning motion, the two participants use their lightly connecting hands to judge what their opponent is doing or might be attempting to do. Has their opponent’s push reached its limit so that they can be safely deflected or are they bluffing; has their own roll back reached a point where going further would result in a loss of balance or can that be used to advantage to make their opponent think they have an advantage—albeit a false one? The permutations and possibilities are many but the intention of the routine is always the same—to create an understanding of energy transfer and when and how to use it in a combat situation.

Curves and circles

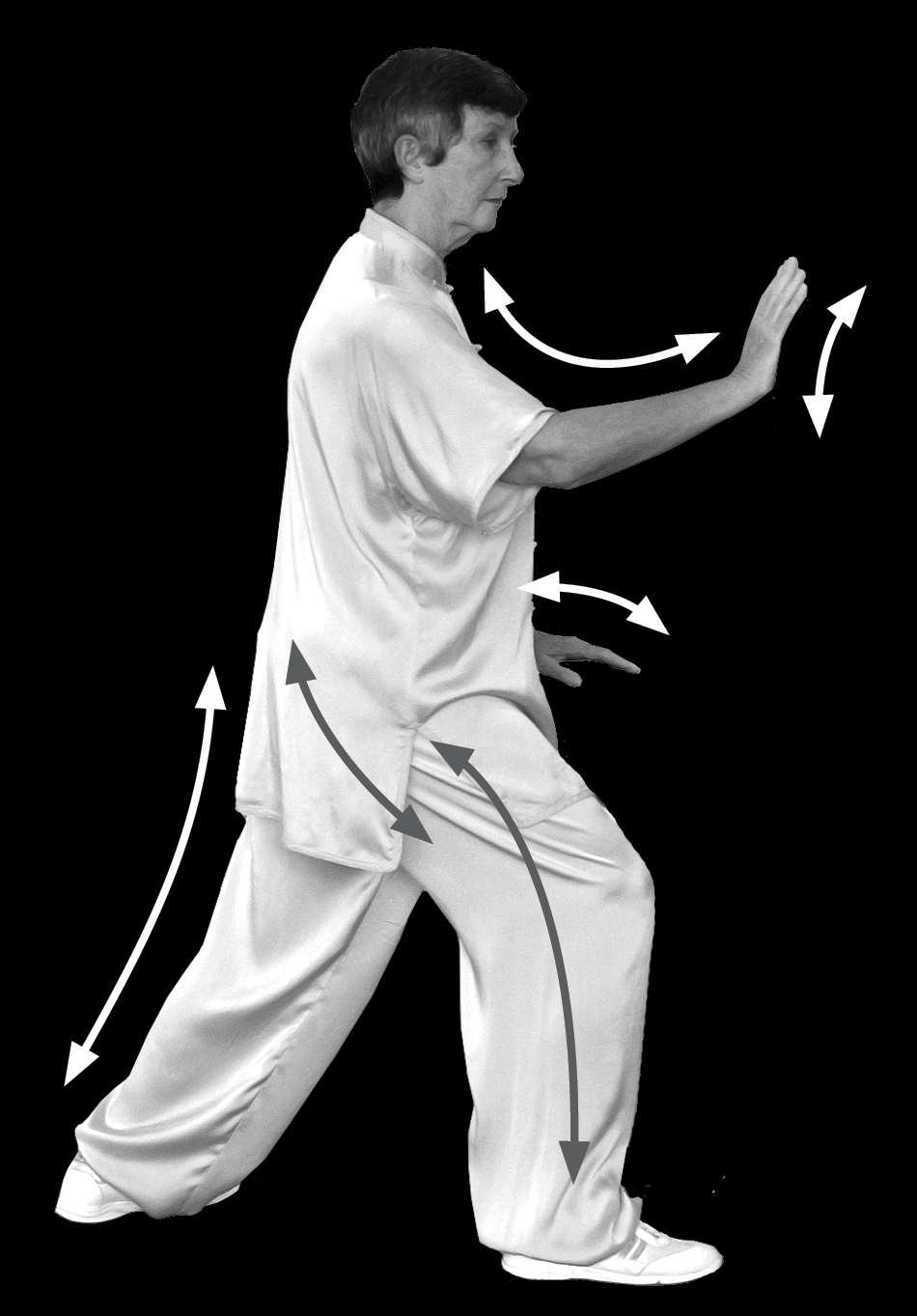

The final aspects to consider concern curves and circles. Carefully observe someone performing Push Hands correctly and it should be obvious that while the torso and head are upright, the limbs are always off-lock and therefore never straight.

The final aspects to consider concern curves and circles. Carefully observe someone performing Push Hands correctly and it should be obvious that while the torso and head are upright, the limbs are always off-lock and therefore never straight.

Energy, either Yin or Yang, can be stored in, and released from, curves but is nonexistent in straight lines. A limb held straight will have no potential. It could be said that its energy has either evaporated or, has become locked in place so that it cannot be released to any effect. In the Push Hands routine, if a leg becomes straight it can cause the foot to break contact with the floor and result in a loss of balance. If an arm becomes straight it becomes weak and of no use for either defence or attack. It is also a strange truth that a curved limb has strength but is relaxed at the same time. Straightened limbs are neither.

The most important curve and circle of all lies in the waist. The waist governs and directs all movements. Without proper implementation, Push Hands for instance would just be two people rocking backwards and forwards, learning nothing and gaining nothing other than sore knees.

Turning the waist creates a circular motion (as already mentioned above) and that circular motion is the second most important component after yielding, in understanding why Taijiquan applications work. Yielding and waist turning go together like the proverbial hand and glove. It is the waist that drives energy from its source in the lower body and delivers it to where it is needed, or conversely, allows energy to be absorbed and stored. Not using the waist will effectively break contact between upper and lower and disrupt coordination between the inner and outer body. Yielding without waist turning will mean that any Yang energy in the lower body will stay there leaving the upper body weakened and having to rely on muscular strength alone. Using the waist correctly will make the difference between and application working or failing and mark the difference between a routine being Taijiquan or just an interesting exercise.